First Encounters

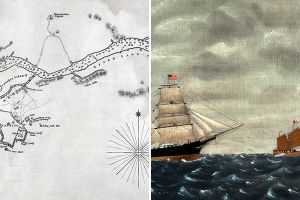

Only five months after the 1783 Treaty of Paris formally ended America’s war for independence from Great Britain, the merchant ship Empress of China sailed from New York’s harbor for Canton (Guangzhou), laden with a cargo of furs and ginseng to trade for China’s fabled tea, silk, and porcelain. That voyage marked the first contact between the fledgling republic and China but was soon followed by dozens of ships sailing from the ports of Baltimore, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Providence, and Salem. For most of the nearly two and half centuries since then, U.S.-China relations have continued to evolve.

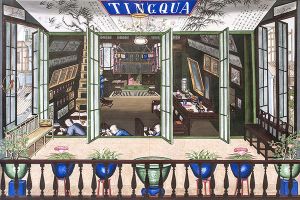

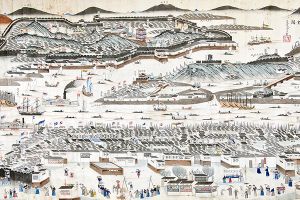

American traders entered into the same arrangements governing the European merchants who preceded them: trade was confined to the port of Canton, foreign residence was initially forbidden, and a Chinese intermediary known as a “compradore” handled all negotiations between foreigners and Chinese. Although the Qianlong Emperor had famously responded that China wanted for nothing when in 1792 Lord Macartney presented King George III’s request for diplomatic and trade relations, China was as eager for foreign goods as foreigners were for the manufactured products of China.

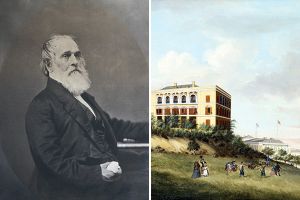

Commercial dealings with China were handled as private transactions by American ship owners. The United States government not only sanctioned the trade, but also supported it by issuing passports requesting safe conduct for the ships and their crews. America’s burgeoning trade with China, though miniscule in relation to each country’s economy, was lucrative for both sides. Soon, U.S. mercantile houses, such as Augustine Heard & Co., built “factories” in Canton to house their imports, their purchases, and their staff.

Following the First (1839-1842) and Second (1856-1860) Opium Wars, additional ports were opened for trade, greatly expanding commercial opportunities and interactions between Chinese and foreigners. American missionaries arriving on cargo ships soon joined their European counterparts and began to move inland, while merchants confined themselves to ports and commerce.

America’s trade with China directly contributed to the development of improved ships capable of safely and swiftly navigating routes to Asia. Navigators aboard vessels charted these courses and the China coast, thereby identifying secure shipping lanes for the many merchants that followed in the wake of the Empress of China.

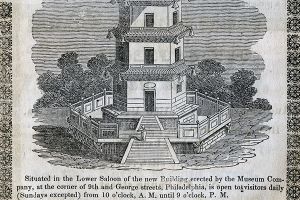

In the United States, “curiosities” acquired by visitors to China were featured in exhibitions and newspapers, and for decades contributed to the impressions Americans gained of a still largely unknown China, as did reports published in missionary journals and talks presented for the paying public by popular lecture circuits.