Military Cooperation

“Good iron is not made into nails; good men are not made into soldiers” was a familiar adage in imperial China, and, indeed, the military did not figure in the accepted social hierarchy of scholar, farmer, craftsman, and merchant. Nonetheless, the Qing government maintained a large military force, but its isolation from advances in military science left it ill-prepared to counter threats to the nation’s stability, particularly in the nineteenth century as the state was besieged by local uprisings and foreign incursions.

By the early twentieth century, both the government and its opponents had turned to Western military advisors, such as Charles “Chinese” Gordon, who was seconded by the British army to help defeat the Taiping rebels, and Homer Lea, an American adventurer-turned-military advisor to the late-Qing Reform Movement. When Reform leaders broke with Lea, he became the primary military advisor to Sun Yat-sen, whose rival Republican movement overthrew the Qing Empire in 1911.

American military experts also served as advisors during the following decades of the Republic of China. General Joseph Stilwell was a military attaché at the U.S. Legation from 1935 to 1939 and, as Commander of U.S. Army forces in China, Burma, and India, worked with Chinese troops from 1942 until 1944. General Claire Lee Chennault created the 1st American Volunteer Group (popularly called the “Flying Tigers” and known for the shark teeth painted on its airplanes) to upgrade China’s air force soon after the United States joined World War II.

Back in the United States, Chinese Americans purchased bonds to provide airplanes for China’s defense during the war. Hundreds of Chinese and Chinese American military personnel even trained near U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s home in Springfield, Illinois, and elsewhere in the United States.

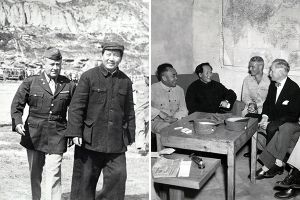

During World War II and the concurrent Chinese Civil War, American military specialists worked primarily with the Nationalists. They also explored an alliance with the Communists. The United States Army Observation Group, known as the Dixie Mission, spent several months meeting with Mao Zedong in the caves of Yan’an, where Mao’s Eighth Route Army had settled after the Long March. The Dixie Mission was an attempt to determine if the United States should liaise with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to win the war, and also to gauge the outcome of the civil war. They were on the whole favorably impressed with the discipline and organization of the Communists, but the mission was recalled. Following Japan’s surrender, the United States extended aid to the Nationalists but refrained from getting deeply involved in the conflict.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949, the U.S. Department of State issued the China White Paper, which stated that the United States had stayed out of the Chinese Civil War because it neither should nor could have influenced the outcome. Though interactions between the two countries continued, they were limited. It would take thirty years before diplomatic relations were reaffirmed.