Cultural Perceptions

After the two Opium Wars in the mid-nineteenth century, the Qing polity could no longer ignore the world beyond its borders. The government gradually acknowledged that engaging with the West was the only viable option for maintaining China’s sovereignty. While fast steam-powered ships that replaced earlier full-masted vessels from abroad hastened U.S.-China interactions, trade and diplomacy were enhanced through cultural exchange.

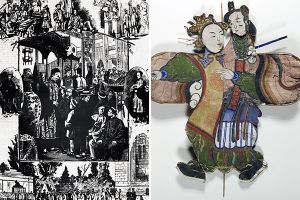

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, international expositions were organized in Paris, Philadelphia, and other venues, where China’s culture and manufactured goods were revealed to most westerners for the first time. The Qing government even dispatched an imperial official to the site dedication of the China Pavilion at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1903.

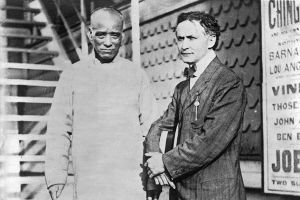

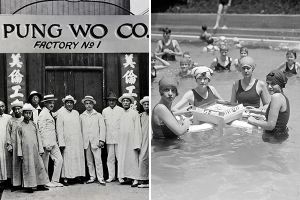

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 drew thousands of Chinese from the coastal province of Guangdong to America. Intending only to sojourn until they struck it rich and returned to their homeland, the Chinese took with them lifestyles that were totally alien to Americans. Their language, their dress, their customs, and their food all marked them as foreign. They continued to be strange but exotic to Americans, although welcomed in limited ways. American views of the Chinese were disparate: from the uneducated immigrant laborer to the refined Chinese known for fine art, glorious costumes, and significant inventions such as gunpowder, silk production, and the wheelbarrow.

To feed their compatriots, some Chinese immigrants opened restaurants, which eventually caught the interest of Americans who were drawn to low prices and unfamiliar flavors. One of the earliest Chinese cookbooks for the American kitchen was written in Boston in 1945 by Buwei Yang Chao and translated by her husband Chao Yuenren, China’s foremost linguist who claimed to have coined the term “stir-fry.” Joyce Chen, a native of Beijing, popularized Chinese cuisine in America with her restaurants, cookbooks, and television program.

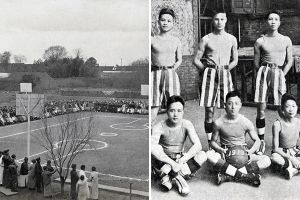

Throughout much of the twentieth century in China, Western culture gradually became associated less with imperialism and more with modernization. Basketball, cinema, music, and Coca-Cola were easily and eagerly grafted onto Chinese mores. Education in schools initially established by missionaries and study abroad experiences exposed young Chinese to ideas that did not necessarily conflict with what were considered Chinese norms. Art, sports, food, and higher education slowly supplanted trade and diplomacy as the primary vehicles for the cultural exchanges that continue to enliven both nations.