Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1956

The opportunity to perform live on radio stations permitted Gillespie and his successors to reach much larger audiences than would otherwise have been possible. It also led to contacts between American musicians and members of the local cultural scene.

Courtesy of the Dave Usher Collection. Photograph by Dave Usher. |

Students react enthusiastically during the concert. Athens, Greece, 1956

Not long before the group’s arrival in the Greek capital, rioting students had stoned the U.S. Information Service office to protest American foreign policy. According to jazz critic Marshall Stearns, who accompanied Gillespie’s group on this first-ever State Department tour, the same young people were so captivated by the charismatic bebopper’s music that they carried him through the streets on their shoulders in triumph. A local newspaper headline proclaimed, Students Drop Rocks and Roll with Dizzy.

Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

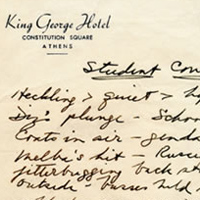

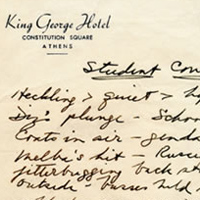

Marshall Stearns’ notes from Athens describe the events surrounding this performance.

Athens, Greece, 1956

Not long before the group’s arrival in the Greek capital, rioting students had stoned the U.S. Information Service office to protest American foreign policy. According to jazz critic Marshall Stearns, who accompanied Gillespie’s group on this first-ever State Department tour, the same young people were so captivated by the charismatic bebopper’s music that they carried him through the streets on their shoulders in triumph. A local newspaper headline proclaimed, Students Drop Rocks and Roll with Dizzy.

Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

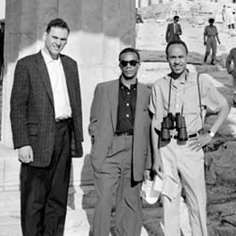

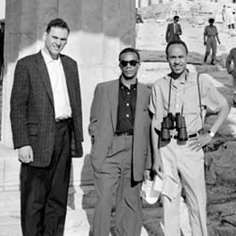

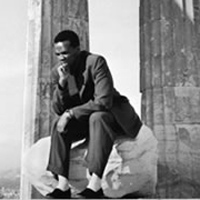

L to R: Rod Levitt, Quincy Jones, and Ernie Wilkins in front of the Parthenon. Athens, Greece, 1956

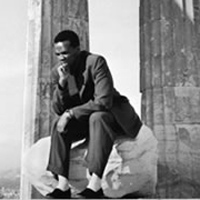

USIS employees relished the opportunity to share local attractions with band members. The musicians enjoyed themselves, reveling in the wonders of the ancient world, and Quincy Jones was inspired to emulate Rodin’s famous sculpture, “The Thinker.”

Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

L to R: Billy Mitchell, Ernie Wilkins, and Quincy Jones: jazz archaeologists! Athens, Greece, 1956

USIS employees relished the opportunity to share local attractions with band members. The musicians enjoyed themselves, reveling in the wonders of the ancient world, and Quincy Jones was inspired to emulate Rodin’s famous sculpture, “The Thinker.”

Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

Athens, Greece, 1956

USIS employees relished the opportunity to share local attractions with band members. The musicians enjoyed themselves, reveling in the wonders of the ancient world, and Quincy Jones was inspired to emulate Rodin’s famous sculpture, “The Thinker.”

Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

Karachi, Pakistan, 1956

To Gillespie, the purpose of his job as a Jazz Ambassador was to bring people together. As he explained in his autobiography, To Be or Not to Bop, his method included having fun, being honest, giving away free concert tickets, and sometimes, as in this instance, playing with different kinds of musicians.

Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

Zagreb, Yugoslavia, 1956

On the Balkan leg of this extensive tour, Gillespie befriended twenty-six-year-old Nikica Kalogjera – just emerging as a major composer and musician. Such encounters with local artists and admirers set the stage for more than two decades of creative interactions by future Jazz Ambassadors.

Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

Nairobi, Kenya, 1973

Representing the United States at ceremonies celebrating the tenth anniversary of Kenyan independence, Gillespie composed a song, Burning Spear, as a tribute to President Jomo Kenyatta. The musician addressed the audience in Swahili, saying that he considered them his people.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 1956

During this brief stop in the Caribbean, band members recovered from a harrowing experience flying through a hurricane. According to the group’s recording engineer and producer Dave Usher, who was along for the ride, the plane dropped precipitously over 1,000 feet and leveled out just before hitting the water. The history of the cultural diplomats’ travels is replete with near misses, uncomfortable means of transportation, illness, and exhaustion. These challenges make their contributions to international understanding all the more impressive.

Courtesy of the Dave Usher Collection. Photograph by Dave Usher. |

Concert program. Athens, Greece, 1956

Not long before the group’s arrival in the Greek capital, rioting students had stoned the U.S. Information Service office to protest American foreign policy. According to jazz critic Marshall Stearns, who accompanied Gillespie’s group on this first-ever State Department tour, the same young people were so captivated by the charismatic bebopper’s music that they carried him through the streets on their shoulders in triumph. A local newspaper headline proclaimed, Students Drop Rocks and Roll with Dizzy.

Courtesy of the Marshall Stearns Collection, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

Dizzy at a reception with Princess Shams Pahlavi, elder sister of the Shah of Iran, and her husband. Abadan, Iran, 1956

In the first stop of the inaugural State Department jazz tour, the band played in this Persian Gulf oil town, meeting national leaders and taking in the sights. The price of this extensive voyage, which also included visits to the Middle East and Southern Europe, led to criticism by some U.S. lawmakers, but the value of this innovative approach to diplomacy was defended by many.

Courtesy of the Dizzy Gillespie Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. |

Kool Kat Diplomat

In March of 1956, bebop trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and his band embarked for Southern Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia on the first U.S. State Department jazz tour. For government officials eager to present a positive image of America abroad, the integrated group was a dream come true. And Dizzy, with his spell-binding virtuosity, arresting solos, and egalitarian sensibilities buoyed by playful humor, won over a wide variety of audiences, from sophisticated fans in Beirut to people in Dacca, East Pakistan, who probably had never before heard jazz. “The language of diplomacy,” argued a Pakistani editorial, “ought to be translated into a score for a bop trumpet.”

Jazz critic and scholar Marshall Stearns accompanied the band and attributed the global popularity of jazz to its anti-authoritarian ethos that transcends rules and regulations. He described the group arriving in Athens to play a matinee for students who had recently stoned the U.S. Information Service office to express their anger at America’s support of Greece’s unpopular government. In spite of the potential for disaster, the young people were so excited by the music that Dizzy later recalled they tossed their jackets in the air and carried him on their shoulders through the streets of the city.

Gillespie delighted in meeting people abroad, from children to musicians. In Karachi, Pakistan, he refused to play until the doors were open to the “ragamuffin children” because “they priced the tickets so high that the people we were trying to gain friendship with couldn’t make it.” Gillespie likewise opened the gates in Ankara, Turkey, declaring “I came here to play for all the people.” Fascinated by local musicians and eager to learn new music, in Dacca, East Pakistan, he heard a child playing a one-string violin with a clay resonator. The band leader took out his horn and wrote down every note, and then invited the young boy to a jam session. In Karachi, Dizzy joined a snake charmer and played for a cobra, while in Ankara he included Ahmed Muvaffak Falay, Turkey’s number one trumpeter, in the concert.

Gillespie and his band traveled to South America in July of the same year. He had long been interested in Latin jazz and was thrilled to visit different regional samba schools and play with an array of percussion instruments from the berimbao, to the cuica, and the tambourine. In Buenos Aires, Dizzy encountered the jazz pianist Lalo Schifrin who told him about the bossa nova movement in Brazil, and later met the creators of that musical style, João and Astrud Gilberto and Antonio Carlos Jobim.

Dizzy made his final State Department tour in 1973 when he traveled to Nairobi, Kenya, to perform at the celebrations of the 10th anniversary of Kenyan independence. He touched local audiences with his composition Burning Spear, written in honor of President Jomo Kenyatta, and by addressing his audiences in Swahili. In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, State Department officials marveled at the Gillespie band’s “openness, sincerity, friendliness, and approachability” and were delighted that the great jazz diplomat had fans “dancing in the aisles.”