The Rest of the Story

Tad Hershorn, Media Archivist

Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

Pick Yourself Up

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers might have been on to something regarding the life or second lives of historic photographs in a song from their 1936 film Swing Time: “Pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and start all over again.”

Historical images, despite this age of visual saturation, can transport the viewer to a particular moment in history. Such is the case with the photos that tell the story of the extraordinary success of U.S. State Department tours featuring some of America’s — and the world’s — premier jazz artists. The “pick yourself up” phase began when Jam Session curators Dr. Curtis Sandberg, Vice President for the Arts at Meridian International Center, and Professor Penny von Eschen, a historian at the University of Michigan, shared the enjoyable task of sifting through thousands of images from leading archives and collections across the United States. The resulting photographs, as well as other documents from the period of the tours, depict the visiting performers interacting with local musicians, the ecstatic audiences who cheered them, and world leaders caught up in the excitement of what jazz was bringing to their countries.

Sandberg visited the Institute of Jazz Studies (IJS) in September 2007, shortly after he began researching the Jazz Ambassadors phenomenon, to peruse the files of IJS founder and State Department jazz advisor Marshall Stearns. He struck pay dirt. Stearns had traveled with, lectured for, and volunteered as an all-around tour guide during the first State Department-sponsored jazz tour — the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra’s concerts in the Near East, South Asia, and the Mediterranean in the spring of 1956. Stearns had preserved his lectures and notes, as well as concert programs and coverage documenting the experience. He also saved his original photographs and negatives that focus primarily on the musicians’ non-performing time. Sandberg did similar research at the Louis Armstrong House Museum at Queens College; the Brubeck Collection at the University of the Pacific in California; the National Museum of American History (Smithsonian Institution), home to the Duke Ellington Collection; the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library at Yale University, the repository of Benny Goodman’s materials; the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, which contains much of the State Department’s cultural files from the period covered by the jazz tours; the Woody Herman Society in Florida; the University of Florida; the University of North Texas in Denton; and with Dave Usher of Detroit, a longtime Dizzy Gillespie friend and associate.

Dust Yourself Off

|

Visitors enjoy Jam Session at Meridian International Center’s opening reception. April 4, 2008. |

Restoring these treasures was my contribution to the exhibition ultimately displayed at Meridian’s elegant galleries in Washington, DC from April through July 2008 and now on tour around the United States and the world. Photo restoration was a key aspect of this process, juxtaposed between the curators’ final selections and the eventual display of the finished images. Photographic restorers often do not have the luxury of printing from original negatives to produce high-quality prints. Instead, they tend to work with vintage photos. Such original materials vary in size and quality, and defects can include tears, abrasions, stains, dust, and scratches accrued over time. There also may be disparities in lighting when flash bulbs highlight one portion of a photograph causing details to disappear into the shadows. In other cases, bright sun-drenched scenes, or white shirts — or even the gleam of musical instruments — may be bleached out. To remedy this, photographs can be cropped to better focus the viewer’s attention on the main subject or even adjusted a few degrees to properly frame an image; contrast and brightness also can be delicately altered. Occasionally, there is a need for stronger measures such as the removal of obstructions. An example was a photograph of the Oscar Peterson Trio in Belgrade in 1973 in which the pianist was partially obscured by microphone stands. This work was carried out after receiving permission from the collection where the original photograph was housed. At other times, additional “field” was added at the edges to provide more breathing space and to make certain that important details were not covered by the mat or frame. Photo restoration can be arduous. Although different than the extremely time-consuming process of fine art conservation, photographic work may take many hours to bring each image back to life. I worked with digitized images ranging between 1200 and 2400 pixels per inch and this aided in the ultimate preservation of every detail.

Three Examples

Preservation is more than the mere mechanics of using Adobe Photoshop. There are philosophical debates surrounding photographic restoration — more than can be addressed in this short essay — and concern the degree of treatment a restorer should undertake. The basic question is how much is enough or too much and at what point does the final result become too “perfect.” I chose a somewhat rigorous path in the hope of making the images “shine” in a way that might have pleased their photographers. However, this did not deviate from the integrity of the historical images and much care was taken to preserve the impact of the originals.

Courtesy of the Brubeck Collection, Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library. Copyright Dave Brubeck. |

The starting point for the photograph of Dave Brubeck accepting a bouquet of flowers at the Baghdad airport in 1958 was a tighter crop of the image, particularly on the left where a partially obscured band member detracted from the main subject. The addition of contrast on the group’s leader and the U.S. Embassy contingent greeting him was highlighted by bringing out details such as the lettering on the aircraft, while keeping contrast subdued so as not to compete with the focal point of the image.

There were many challenges in restoring the 1956 photograph of Benny Goodman with Thai dancers in Bangkok. The lighting on the two female dancers on the right leaves them in the shadows. Selectively manipulating contrast or light level was accomplished by isolating an area of the picture and correcting only that portion. Another technique that I refer to as “scrubbing” permitted me to salvage mid-range or light tones hidden within deep shadows such as those on the dancers’ garments. Goodman’s white suit coat was selectively darkened to distinguish the jacket from his white shirt. Magnification in Photoshop also enabled me to bring out the white of the male dancer’s eyes, one of many small details that, combined, brought the photograph back to life.

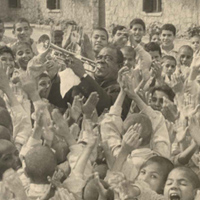

Louis Armstrong performing for patients at a Cairo children’s hospital in 1961 emerged as the keynote picture of the Jam Session exhibition. The most significant goal was to center Armstrong in the frame, surrounded by the joyous faces of children hearing “Satchmo” for the first time. This was accomplished by cropping the foreground filled with the backs of children’s heads that diverted attention from the main action. Louis was also made to stand out by subtly isolating his figure and adding five percent contrast, as well as reducing this on the remainder of the photo by the same percentage.

Start All Over Again

The next leg of the journey takes us to Chattanooga, Tennessee, the home of James Schoonmaker’s 204 Studios where the exhibit prints were produced. He worked closely with Curtis Sandberg and his Meridian colleague Terry Harvey and printed numerous small images that were subsequently framed together, in some cases alongside copies of historical documents to tell stories about the tours. Schoomaker also created spectacular large-format prints that can be likened to signposts once experienced along the international highways when Jazz was king — if even for treasured days gone by. Now that the Jam Session has begun its national tour, soon to be followed by facsimile exhibits created by Meridian and circulated internationally by the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State, those hallowed days will ride again.