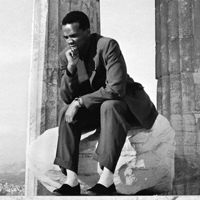

The power of jazz

Quincy Jones

Los Angeles, California

One of my happiest recollections is when the U.S. government in 1955 asked Dizzy Gillespie to organize a band that would travel to Southern Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia as America's first Jazz Ambassadors. Dizzy was booked on a Jazz at the Philharmonic tour of Europe and was unable to recruit and rehearse the group. Since we had a history of working together he asked me to do it and, at the age of 22, I levitated. At the time, I was working on the first record by a 17-year-old unknown track jumper from San Francisco named Johnny Mathis. After I got the request from Dizzy, I explained to George Avakian that “my Nation” (Diz) had called and I had to decline the offer of working with Johnny.

Over several months, I found the best jazz musicians in the United States, reworked some of the older arrangements, wrote new ones, plus had band members like the great Melba Liston and Ernie Wilkins compose original charts. We wrote arrangements for the national anthems of every country we visited and also composed a piece representing “The History of Jazz.” We picked up Diz in Rome in March of 1956 and continued on to our first gig in Iran. The band was ready to play.

The entire trip was an adventure. We didn't know what we were getting into; neither did the State Department. It was new for everyone. While we expected to encounter leaders, we also wanted to meet the people. From Pakistan to Iran, Syria, and Yugoslavia we had a great time — learning about local customs, jamming with each country's musicians, and letting the music bring us together. We became the kamikaze band representing our country. I say that because there was conflict of some kind going on in every place we visited.

They were so pleased with our tour accomplishments that we were asked to make another trip that summer. We visited South America where, again, jazz helped us to build bridges and tell a larger story of America — and ourselves — to people from all walks of life. Music and art have that kind of power — and the fact that the State Department adopted this model for decades after our 1956 tours means that it worked.

There is no substitute for these kinds of personal exchanges — especially those based on the arts. They allow us to better understand one another, to respect and value our differences, and more importantly, our similarities. They also do this on a profound level that can change attitudes and beliefs. Believe it or not, some of these countries had never seen or heard trumpets, trombones or saxophones play together.

The jazz tours, many over fifty years in the past, may not be known by some Americans, especially the very young. That is why I am pleased Meridian International Center has organized Jam Session for travel around the country and the world. This exhibit captures America's jazz greats as they shared their spirit with the people of the world — and shows how music can create lasting connections.