Seeking Truth and Unity

In the early phase of globalization, nineteenth-century cosmopolitan thinkers in the United States and India sought to articulate a universally inclusive cosmology, recognizing the common core of all religions. Rammohun Roy, for example, seeking spiritual renewal for a new age of enlightenment, turned to the fundamental universalism embedded in ancient Sanskrit scriptures. He also looked for inspiration in the teachings of other religions. In dialogue with American Christian Unitarians, he found especially congenial ideas, and the Unitarians, in turn, published Roy’s essays in prominent American periodicals.

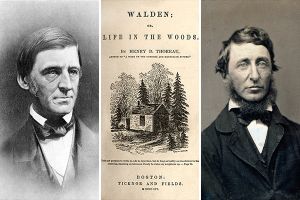

American intellectuals welcomed English translations of Sanskrit literature, philosophy, and theology that inquisitive mariners and travelers brought aboard trading vessels. Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, as well as poets Walt Whitman and John Greenleaf Whittier, read these translations of the Laws of Manu, the Bhagavad Gita, the Vishnu Purana, and the Upanishads. In their quests to grasp the unity of humankind and the divine order, they found this literature inspirational. Thoreau brilliantly captured this meeting of minds in a metaphor inspired by the American ice trade with India:

In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat-Geeta … I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the … priest of Brahma and Vishnu and Indra … and our buckets … grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.

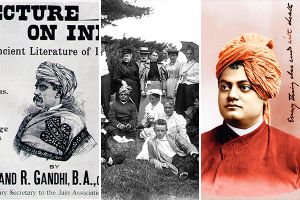

At the end of the century, the first World’s Parliament of Religions, held in conjunction with the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, ushered in a new wave of American interest in Indic thought. Five participants from India attended the assembly. Virchand Gandhi, a scholar and barrister, was well received as he spoke on the history and beliefs of his own sect, Jainism, and on current issues, including the status of women. When the Hindu monk, Swami Vivekananda, took the podium and opened his address with “Sisters and Brothers of America,” the entire delegation rose in a spontaneous ovation.

During Nobel laureate, poet, and educationist Rabindranath Tagore’s visits to the United States in the early twentieth century, his message followed in the same vein. He underscored the critical importance of freedom, broad-minded education, and universal humanism as a moral compass in an age overwhelmed by industrial growth and imperial ambition. Tagore found much to admire in American pragmatism.

Many Americans traveling in India found the ashram way of life inspirational. In 1938, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s daughter Margaret visited India. She was so moved by the spiritual community that she remained in Auroville, near Puducherry, until her death six years later. Similarly, E. Stanley Jones, a Methodist missionary and an intimate friend of Gandhi, later adopted the ashram concept to create Christian spiritual communities both in the United States and India.