Toward Freedom

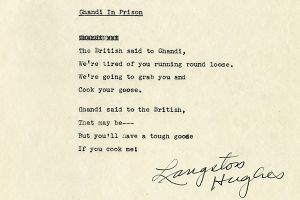

When the United States gained its independence, American and Indian aspirations for self-determination became linked in a web of connections. In 1801, a group of grateful clients presented Ramdulal Dey, Calcutta’s leading agent for the American trade, with a life-sized oil painting of George Washington, the military leader of the American Revolution and first president of the new nation. Prominently displayed in Dey’s north Calcutta mansion, the painting stood as a reminder that colonies could earn their freedom. Almost a century later, Mahatma Gandhi took inspiration for his program of non-violent resistance to colonial rule from another American. Henry David Thoreau’s writing on civil disobedience provided a powerful tool in the struggle for India’s independence. In turn, Martin Luther King Jr. adapted Gandhi’s strategies to devise a path for the African American civil rights movement.

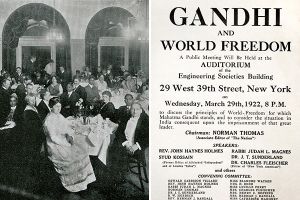

Many Americans followed developments in India’s emergent freedom movement in the first decades of the twentieth century with interest and sympathy. When Lala Lajpat Rai, one of its pioneers, visited the United States, he met with people from all walks of life, and read voraciously. In his book, The United States of America (1916), he devoted chapters to education, religion, race, and the status of women. Around the same time, the cover of The Hindusthanee Student, a quarterly published in Chicago, featured a statement from William H. P. Faunce, president of Brown University. He endorsed the increasing depth of Indo-U.S. dialogue: “Our American students could learn much from the Hindusthanee students … The East and the West are like the right hand and the left. Only when both are clasped will the great world-task be achieved.”

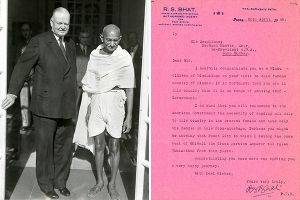

World War II brought new complexities, boosting freedom struggles across the globe and stationing American troops in India. Franklin Delano Roosevelt became the first American president to openly support Indian independence, though he did so cautiously in deference to the critical alliance between the United States and Great Britain. In 1942, understanding Indians’ hesitation in joining the Allied forces without the promise of freedom, the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee issued a statement supporting autonomy for India. After the war, U.S. President Harry Truman made a point to include India in American efforts to alleviate hunger, sending former president Herbert Hoover to assess India’s needs in consultation with Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi.

When Indian independence was declared in 1947, the United States and the Republic of India were at long last able to engage in full diplomatic relations, greatly expanding the scope and opportunity for cultural and educational exchanges. The United Nations marked the momentous event and welcomed the sovereign Republic of India. Dr. Padmanabha Pillai, India’s first representative to the U.N., raised his country’s national flag, which Nehru hailed as “a flag not only of freedom for ourselves, but a symbol of freedom for all people.”