Finding Inspiration

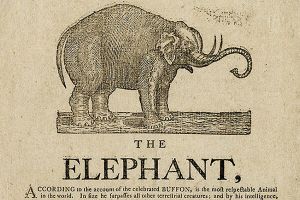

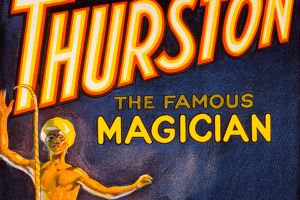

From magic to cinema and dance, in virtually all areas of entertainment, artists and audiences in the United States and India found inspiration and enjoyment in each other’s productions. The first elephant exhibited in the United States, brought from Calcutta in 1796, was the star attraction of a hugely successful tour. In the early twentieth century, America’s leading magician, Howard Thurston, visited India to see its famed practitioners of illusion and from this experience crafted his own version of the Indian ‘rope-trick.’ In the 1920s, African American performers brought jazz to Bombay, where it was quickly embraced by Indian audiences and musicians. Yet, in the period before India’s independence, it was in cinema and dance that the most productive cross-fertilizations took place.

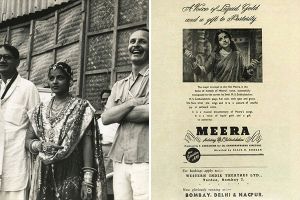

Hollywood and Bollywood – twin capitals of the world film industry – have benefited from a remarkable range of connections. In 1935, young film director Ellis R. Dungan set out for India at the suggestion of Manik Lal Tandon, a classmate in the University of Southern California’s Department of Cinematography. Dungan stayed on for fifteen years, applying his American training to make Tamil and Hindi films. Actors also pursued crossover careers, carefully managing their identities to suit their ambitions. The famed Oscar nominee, Merle Oberon, opted to conceal her Bombay Anglo-Indian origins and school days at Calcutta’s La Martiniere to become a leading lady in Hollywood. By contrast, Sabu Dastagir, the son of a mahout in princely Mysore who first appeared on screen at age thirteen, built a Hollywood career in roles that dramatized his Indian identity, most famously as Mowgli in the film adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book.

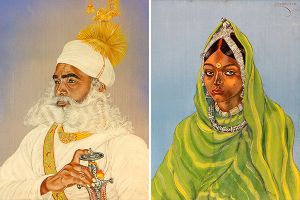

The international modern dance movement and the renaissance of Indian classical dance emerged concurrently in the early twentieth century. Modern dance pioneer Ruth St. Denis first saw Indian performers at Coney Island in New York. She was instantly enthralled. Experimenting with poses depicted in paintings and photographs of Indian dancers, St. Denis brought her ‘Hindu’-style performances to Europe and eventually to India. Some credit her zeal for Indian dance as a stimulus to the revival of traditional forms. Uday Shankar, brother of sitar master Ravi Shankar, initiated modern dance in India by blending local traditions and Western styles. Uday was the first Indian dancer to perform in prominent European and American venues, and leading American impresario Sol Hurok managed his highly acclaimed U.S. tour in the 1930s.

Around the same time, Ragini Devi, born in Michigan as Esther Sherman, emerged as a self-taught exponent and scholar of Indian dance, publishing Nritanjali: An Introduction to Indian Dancing in 1928. Two years later she arrived in India, where she began a life-long program of performance and pursued wide-ranging research into India’s myriad dance traditions. Ragini Devi, along with Uday Shankar and Ruth St. Denis, was among the small group of pioneering performers who revived, reinterpreted, and internationalized Indian dance for the new century.