L to R: Win Oo, famous singer and film star; Sandaya Hla Htut, composer and pianist; Basie; unidentified man; U Than Myint, Deputy Director, Burma Broadcasting Service. Rangoon, Burma, 1971

Basie’s Orchestra visited Burma and Laos for the State Department after a commercial tour of Europe and other Asian countries. The band leader performed his arrangement of this song, together with local musicians and singers, at well attended concerts in Rangoon.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

Manila, Philippines, 1975

The performance captured in this image was part of a long-standing history of official musical collaborations between the two countries. Filipino jazz had been developing since the early twentieth century, largely through the efforts of Walter H. Loving, an African American officer in the U.S. Army, who led the world-famous Philippine Constabulary Band from 1901-1923.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

Rawalpindi, Pakistan, 1975

This tour launched U.S. Bicentennial activities in Pakistan, Turkey, Jordan, Syria, Egypt, Iran, and Kuwait. Pakistani media pronounced the group “stunning,” and one American Foreign Service officer declared that the State Department “couldn’t have chosen better Ambassadors of American culture

than the Benny Carter Quintet.”

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

L to R: John B. Williams (bass); Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison (trumpet); Professor Morroe Berger (lecturer); Benny Carter; Margaret Carter; Millicent Browne (vocalist); Earl Palmer (drums); Gildo Mahones (pianist); Erol Pekcan (Turkish musician and producer). Ankara, Turkey, 1975

The group gave two concerts to packed houses in the auditorium of the Turkish-American Association in an event sponsored by Turkish jazz expert Erol Pekcan. The highlight of the first performance took place when three local musicians played with the band at Carter’s invitation.

Courtesy of the Benny Carter Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. |

Benahmed, Morocco, 1962

Cozy Cole’s sideman brought more than musical talent to the tour. His unique approach to cultural diplomacy was well received by children and adults and underscores the creativity of the Jazz Ambassadors in making friends for America.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

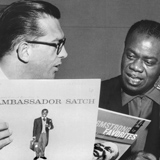

Washington, DC, mid-1950s

At the time of his death in 1996, the New York Times lauded Conover as the most famous American in the world. His weekly Voice of America jazz radio show began in 1955 and soon reached 30 million people in 80 countries. Within a decade over 100 million listeners avidly followed these broadcasts.

Courtesy of the Willis Conover Collection, the University of North Texas Music Library. |

Washington, DC, mid-1950s

At the time of his death in 1996, the New York Times lauded Conover as the most famous American in the world. His weekly Voice of America jazz radio show began in 1955 and soon reached 30 million people in 80 countries. Within a decade over 100 million listeners avidly followed these broadcasts.

Courtesy of the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

Washington, DC, mid-1950s

At the time of his death in 1996, the New York Times lauded Conover as the most famous American in the world. His weekly Voice of America jazz radio show began in 1955 and soon reached 30 million people in 80 countries. Within a decade over 100 million listeners avidly followed these broadcasts.

Courtesy of the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

Santiago, Chile, 1958

As lyricist Iola Brubeck had written in the 1962 jazz musical, The Real Ambassadors, “. . . And when our neighbors call us vermin, we send out Woody Herman.”

Courtesy of the Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. |

Bands-eye view of the crowd held back by police. Elisabethville, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1966

In parts of Africa, jazz musicians and their State Department partners encountered the unwelcome dilemma of segregated concert venues along with the continuing strain of war.

Courtesy of the Woody Herman Society. Photographs by Bill Byrne. |

The State Department Does it All

Many musicians served as Jazz Ambassadors between the mid-1950s and the late 1970s when the State Department program ended. In this exhibition, images of renowned performers such as Count Basie, Charlie Byrd, Benny Carter, Woody Herman, Clark Terry, Randy Weston, and even university jazz bands tell the story of their travels throughout the world.

Clarinetist and band leader Woody Herman visited Latin America for the State Department in 1958, and continued to delight audiences on a far-reaching tour of Africa in 1966. In Northwest Africa, Herman and his orchestra relished the opportunity to play with locals and to blend instruments from different musical traditions. The following year Randy Weston also made an extensive trip around Africa. In Algiers, he talked with reporters about his interest in Pan-Africanism and African music, explaining that this genre had given birth to jazz. He further noted, “if there had not been any Africa there would not be any jazz.” U.S. embassies praised Weston’s skills as an ambassador, and one official noted that “jazz speaks in a special idiom” and is uniquely effective in communicating American ideals to Africans.

State Department officers similarly appreciated the unique appeal of guitarist Charlie Byrd’s ensemble in Dahomey, suggesting that Byrd’s involvement with Brazilian music and the band’s performance of bossa nova compositions had meaning for listeners in this West African nation because of its “strong historical and cultural ties with Brazil.” Byrd was equally effective on his 1975 Asian tour where U.S. government representatives feared that his popular appeal would exhaust the number of tickets available. In Rangoon, hundreds of young people climbed fences and onto rooftops to reach box offices more quickly. Officials at American embassies around Asia commended Byrd and were delighted by his group’s ability to communicate with musicians in host countries. An excellent example was his participation in a workshop for 150 members of the Singapore Guitar Society.

Benny Carter and his group opened U.S. Bicentennial celebrations in the Middle East and South Asia in 1975 and 1976. At performances in Ankara and Cairo, Carter asked several local musicians to play with the band. Later, the Pakistani newspaper Viewpoint declared that the American Cultural Center in Lahore “couldn’t have chosen better ambassadors of American culture than the Benny Carter Quintet.”

Clark Terry and his Jolly Giants made the last extended State Department jazz tour, reaching Southern Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia in 1978. Terry and his band took advantage of every possible opportunity in Pakistan to connect with people from all walks of life. In Lahore, he invited three well-known artists – a tabla player, a clarinetist, and an accordionist – onstage for an impromptu jam session, merging Pakistani and American musical expressions. On the group’s night off, they played a free concert for personnel at their hotel. In the grand finale of two remarkable decades of touring by the Jazz Ambassadors, Terry then flew to Bombay to head-up an ensemble consisting of musicians from over ten countries at the Bombay Jazz Yatra – a festival that signaled the growing internationalization of jazz music.

Ron Zito (drums), Woody (clarinet), and the band perform for spectators and security forces. Elisabethville, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1966

In parts of Africa, jazz musicians and their State Department partners encountered the unwelcome dilemma of segregated concert venues along with the continuing strain of war.

Courtesy of Special Collection, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

Swinging at the Gezira Sporting Club. Cairo, Egypt, 1966

The Herman Orchestra enjoyed the cosmopolitan scene in the Egyptian capital, where percussionist Yehya Khalil had founded his Cairo Jazz Quartet in 1957. As jazz scenes developed around the world during the 1960s and 1970s, visits by American cultural envoys were catalysts for internationalizing this musical genre.

Courtesy of the Woody Herman Society. |

Woody contributes to the local sound. North Africa, 1966

In this rare image Woody and his band meld the instruments and music of two different cultures.

Courtesy of the Jack Siefert Woody Herman Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. |

Lomé, Togo, 1973

University jazz bands also served as State Department musical ambassadors. Like many of their more famous counterparts, they dazzled audiences and showcased jazz education in schools. Avant-garde clarinetist Batiste recognized the value of collaborations with musicians abroad.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

L to R: Hilton Ruiz (piano; not visible); Clark Terry (trumpet); Victor Sproles (bass); Ed Soph (drums); Chris Woods (saxophone). Karachi, Pakistan, 1978

On this last extended State Department jazz tour before the program ended in 1978, Terry relished the opportunity to meet and play for people from all walks of life. After Pakistan, he flew to India to lead an international band on behalf of the U.S. government at the Bombay Jazz Yatra.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

The band arrives at the Tunis-Carthage airport. Tunis, Tunisia, 1968

Members of the Quintet arrived shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and eulogized the slain leader at their concerts.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

Bringing down the house at the Salle des Fêtes. Nabeul, Tunisia, 1968

Members of the Quintet arrived shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and eulogized the slain leader at their concerts.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

Yaoundé, Cameroon, 1967

Foreign Service personnel faced major challenges keeping pianos tuned and operational in tropical regions. In one instance in Cameroon the instruments rotted and fell apart, leading a USIS official there to plead with Washington not to send any more pianists.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |

Libreville, Gabon, 1967

Weston’s passion for bringing jazz to the world was nurtured in Brooklyn, New York, where he grew up hearing this music in the homes of Thelonious Monk and Max Roach, and frequenting the Putnam Social Club with Monk, Roach, and Dizzy Gillespie.

Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. |