Quincy Jones, Los Angeles, California

Does jazz have a healing role in a world divided by conflicting ideologies?

Dr. Curtis Sandberg

Senior Vice President for the Arts

Meridian International Center

More than 50 years ago, at the height of the Cold War, there was little room for intercultural dialogue — and U.S. government officials looked at how to bridge the gap. European powers were giving up long-held possessions in Asia, Africa and the Pacific, and a competition developed between the Soviet Union and the United States to court these newly independent nations.

One of the ways the USSR accomplished this was through culture — folk and classical music, and an established school of dance. In this battle for the “hearts and minds” of the world's peoples, the United States developed an unlikely but remarkably effective response to Soviet initiatives: building international friendships through jazz. Music that was unique to America and represented a fusion of African and African-American cultures with other traditions was a democratic art form that helped others to understand the open-minded and creative sensibility of our country.

As a first salvo in a program that would continue for more than two decades, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. proposed that Dizzy Gillespie form a big band to represent the U.S. as musical envoys. The State Department and the Eisenhower Administration agreed and the group embarked for Southern Europe and the Middle East in 1956. Dizzy and his orchestra were consummate ambassadors — touching people from all walks of life. From planned encounters with high-ranking officials to spontaneous exchanges with children, the musicians were determined to make friends and did so successfully. One enthusiastic Gillespie concert attendee in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, was moved to exclaim, “What this country needs is fewer ambassadors and more jam sessions!” Jazz diplomacy had begun and the U.S. government was captivated.

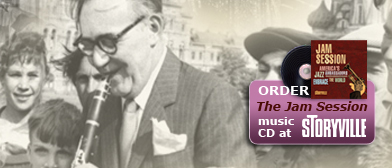

Later the same year, Benny Goodman and his band traveled to East Asia; in 1958, the Dave Brubeck Quartet visited Eastern Europe, the Middle East and South Asia; Louis Armstrong and the All Stars toured Africa in 1960-1961; and Benny Goodman packed his bags again, setting off for the Soviet Union in 1962. The following year, the Duke Ellington Orchestra and its charismatic bandleader crisscrossed the Middle East and South Asia — beginning a decade of journeys. These dynamic cultural diplomacy initiatives continued under the direction of the State Department until 1978, and countless jazz musicians, including Benny Carter, Miles Davis, Woody Herman, Earl Hines, Oscar Peterson, Clark Terry and Sarah Vaughan, circled the globe on America's behalf. They braved political instability abroad and weathered illnesses and exhausting journeys; most were extraordinary ambassadors. Thousands of U.S. government employees made certain concert halls were secured, pianos were available (and tuned) and bands were briefed and well treated. Many retired career Foreign Service Officers fondly remember their role in promoting these activities, and many musicians characterized the trips as the highlight of their careers.

To honor the remarkable achievements of these renowned American musicians, on April 4, 2008, Meridian International Center in Washington, DC inaugurated a photographic exhibition, Jam Session: America's Jazz Ambassadors Embrace the World. Developed in collaboration with University of Michigan professor Penny M. Von Eschen and drawn from collections around the United States, the presentation contains more than 100 images capturing memorable moments from jazz tours to 35 countries and four continents. These include Dizzy straddling a motorcycle with a famous Yugoslav musician; Louis meeting a revered national leader in Nigeria; Benny entertaining kids in Moscow's Red Square and much more. It is the first time that photographs representing this positive experience in American cultural diplomacy have been collected for a single exhibit.

Meridian's mission of promoting international understanding through the exchange of people, ideas and the arts embodies the spirit of the U.S. State Department's jazz program and inspired the creation of Jam Session. Those who will view the show during its national and worldwide tours will experience firsthand how the creative employment of the arts can further international and intercultural understanding. The exhibit honors those who served then, while offering inspiration for outreach efforts today — a time in which worldwide challenges, while different from those of the 1950s, '60s and '70s, are in many ways remarkably similar.